How DATA Act implementation is opening up federal spending

By

Guest Blogger

Posted:

|

Transparency & Data

By Becky Sweger. This post originally appeared on 18F.

In May 2014, President Obama signed the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act (DATA Act) into law. Once implemented, the DATA Act will make it easier to understand how the federal government spends money. The Department of the Treasury and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) are leading the implementation, and Treasury has partnered with 18F Consulting to help with a few aspects of the project:

- Lead outreach for Treasury’s online collaboration space that solicits public feedback about federal spending data.

- Coach vendors and Treasury team on developing pilot projects using agile methodologies.

- Organize and develop the first DATA Act pilot that uses real agency financial and awards data.

- Request for Proposal (RFP) Ghostwriting.

- Perform three to four weeks of user research and discovery to better understand the different audiences and their needs when accessing federal spending data.

The first order of DATA Act business on this blog, however, is to explain what this law is and why it’s important.

According to the Citizen’s Guide to the Fiscal Year 2014, the government spent $3.8 trillion last year. For most people, that $3.8 trillion figure has little practical value — we need more detail to really understand federal spending. What kind of programs and projects does the federal government fund? Who’s getting the money? What local businesses have federal contracts? Are those amounts increasing or decreasing?

Right now, these questions aren’t easy to answer. The DATA Act intends to change that.

Why it’s hard

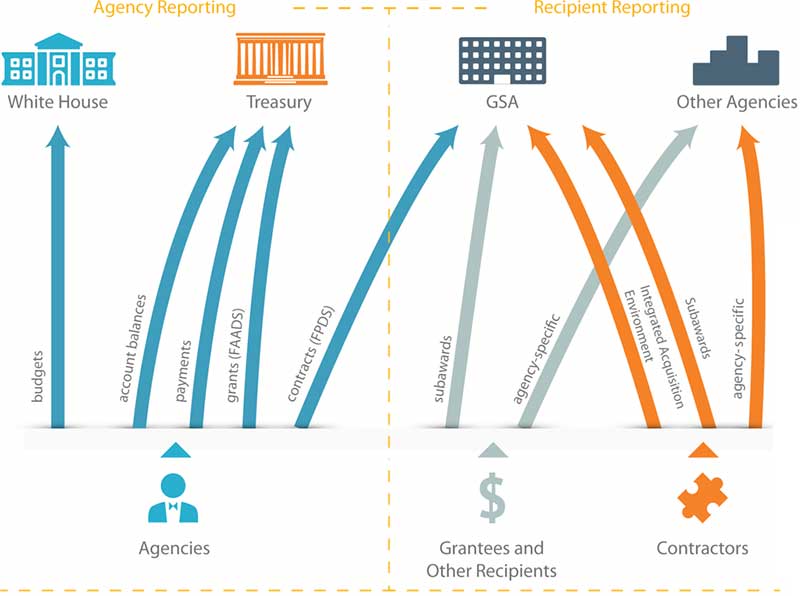

The federal spending lifecycle has many steps, and there are many systems in place to track money as it moves from a congressional appropriation to an actual payment. These systems don’t have a common way to tie money back to specific programs and projects, and that’s what the DATA Act proposes to fix.

Image courtesy of the Data Transparency Coalition

For example, let’s say Congress appropriates $30 billion for student financial aid as part of the annual budget. That $30 billion gets a Treasury account number (officially called a Treasury Account Symbol or TAS), and the applicable agency can start deciding how to use it. In this case, that agency would be the Department of Education, and throughout the year it will use the $30 billion to grant individual student financial aid awards.

However, the Department of Education — like all agencies — doesn’t use the Treasury Account Symbol as the only way to categorize money. Because the Department uses that $30 billion of financial aid money to fund several different initiatives, the Department may allocate those dollars to more specific buckets like Pell grants, work-study, and scholarships for veterans’ dependents.

.jpg)

When Treasury pays money to a recipient of student financial aid, it debits the money from the high-level $30 billion account. The specifics live within the Department of Education and aren’t associated with Treasury’s payment records. In this context, think of the Treasury like a bank. It keeps account of the money your agency (or program) has, but you're responsible for keeping track of what the payments mean.

As a result, we can answer questions like “how much did the U.S. spend on student financial aid last year?” But we can’t answer some of the more interesting questions without digging into the financial and awards systems at individual agencies:

- Which universities received Federal Work-Study funds last year?

- What’s the ten-year trend for total Pell grants awarded?

How the DATA Act will help

There’s nothing wrong with agencies organizing money differently than the high-level Treasury accounts. Agencies do (and should) have the autonomy to track their appropriated funds in a way that aligns with how they deliver services. The DATA Act won’t change that.

Instead, the DATA Act mandates a common federal spending data standard. A simple way to think of this common data standard (though it’s much more nuanced) is a list of spending information that agencies must track each time they award money. The list will include awards-level information (specifics about the program or project being funded, who and where the money is going to, etc.) as well as information about the Treasury account that the award was paid out of.

Agencies have all of this information, but it usually lives in several different systems. The DATA Act requires them to pull it all into a single format (i.e., the federal spending data standard) and periodically submit it to Treasury. This will be hard work. But once the DATA Act is implemented, there will be one single place that houses information about the broader spending lifecycle for the entire federal government. This single place will be USASpending.gov (or a replacement website), where the public will be able to:

- Track dollars actually spent against the dollars appropriated by Congress

- Track overall spending by high-level categories such as personnel compensation and contracts

- Find out how much money is available in a Treasury account

The DATA Act is a large undertaking, and it will be several years before this unified picture of federal spending emerges. Treasury is laying the groundwork during this early stage of the work to ensure an open-source, transparent, and user-centric implementation and is promoting a standard that will be able to evolve as the federal government changes. 18F is excited that the data standard is being developed in a way that matches our values — openly and iteratively — and is proud to be a part of the team.

By working in this fashion, the public will have a source for information that meets their needs in both the short-term and as the project naturally evolves. Building the common data standard this way should also save the government millions in development costs, and planning for evolution and iteration in the data standard will save even more. 18F is proud to be a part of this effort and looks forward to working with Treasury to make the process a meaningful and effective one.