Ignoring Youth Unemployment

Nov. 15, 2012 - Download PDF Version

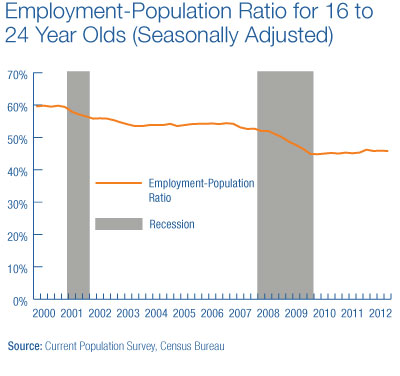

The challenges facing this generation extend beyond education. The Great Recession hit young Americans hard over the past five years, leaving 16- to 24-year-olds with an unemployment rate of 16 percent — more than twice the national average.21 The unemployment rate jumps to 17 percent for Latino youth and 26.7 percent for African American youth.22 And the problem is worse than these unemployment rates would suggest. The federal government counts people as unemployed only if they have recently looked for work, leaving out millions driven from the labor force by persistent lack of opportunity. The proportion of all young adults ages 16 to 24 with any type of job fell during the decade leading up to the Great Recession, when the employment rate plummeted to the lowest levels on record.23 Even now, less than half of this population is working (Figure F).24 These statistics are especially alarming, given that high youth unemployment leads to lower wages for years to come.25

Rampant youth joblessness contributes to a trend of "disconnected youth" — young people who are neither working nor in school. Disconnection from productive activity has deleterious consequences for a young person's future. When young people miss out on skills and work experience, it contributes to lower incomes, worse health outcomes, and higher poverty and crime rates.26 Over 6.7 million young people across the country are currently disconnected27 — a fact that is likely to have significant consequences for our economic future. Over their lifetime, these disconnected youth will cost taxpayers $1.6 trillion in public expenditures in criminal justice, health care, and safety-net assistance.28

Over 6.7 million young people across the country are currently disconnected27 — a fact that is likely to have significant consequences for our economic future.

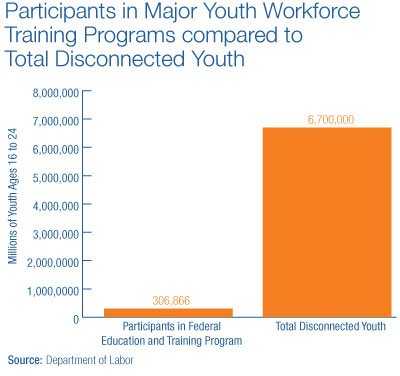

Yet, we invest little in getting this generation back to work. The major employment and training programs targeted at disadvantaged youth serve less than 5 percent of the disconnected population (Figure G).

Workforce Investment Act (WIA) Youth Activities, JobCorps, and YouthBuild are the three major federal initiatives to help disadvantaged youth develop skills and pursue an education. In 2011, WIA Youth Activities-funded programs increased average earnings of participants who found jobs by an annualized $4,031, as compared to their earnings before they entered the program.29 Almost three-quarters of JobCorps participants obtain full-time employment or go on to further education,30 and YouthBuild returns up to $43.90 in social benefits per dollar invested for youth involved with the juvenile justice system.31

Programs to help disconnected youth develop workplace skills cost $2.4 billion in 2012. We spend more than that annually on tax breaks for oil and gas companies.

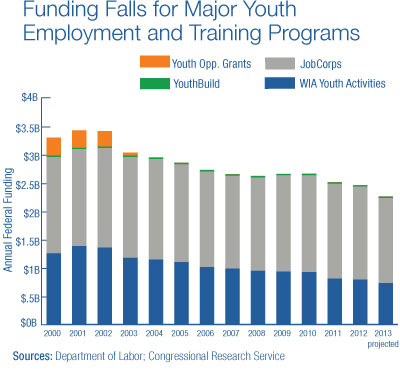

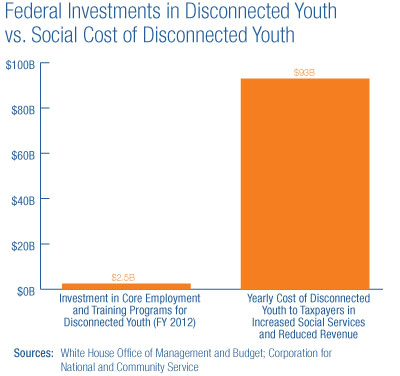

Despite the obvious benefits youth jobs programs have for disconnected youth and for the American economy, and even as employment rates have fallen for young people, the federal government has reduced investment in disadvantaged youth. Adjusted for inflation, core funding has fallen by $1 billion over the past decade (Figure H), from $3.46 billion in FY 2002 to $2.5 billion in FY 2012. Youth Activities suffered a 43 percent funding drop during that time, while the Youth Opportunity Grants program was eliminated entirely after 2003 (Figure H). As these programs are cut, disconnected youth see fewer and fewer opportunities to get back on track. In 2011, disconnected youth cost taxpayers $93 billion in lost revenues or increased social services, or 3,000 percent more then the major education and training programs to help disadvantaged youth contribute productively to society (Figure I).32

Even as funding for these programs has fallen over a decade, if sequestration takes effect, Youth Activities, YouthBuild, and Job Corps will see an estimated additional $196 million in cuts in 2013.34 Continued disinvestment in this crucial area increases the number of youth with limited options - stunting their economic prospects for the years ahead - while simultaneously placing a greater burden on American taxpayers.

ENDNOTES

21 "Labor Force Statistics including National Unemployment Rate," Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed October 29, 2012, http://www.bls.gov/data/.

22 "Labor Force Statistics including National Unemployment Rate," Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed October 29, 2012, http://www.bls.gov/data/.

23 See Adrienne L. Fernandes-Alcantara, Youth and the Labor Force: Background and Trends, (Washington D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2010) 12; see also Andrew Sum et al., The Historically Low Sumer and Year Round 2008 Teen Employment Rate: The Case for an Immediate National Public Policy Response to Create Jobs for the Nation’s Youth, (Boston: Center for Labor Market Studies, 2008) 4.

24 "Labor Force Statistics including National Unemployment Rate," Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed October 29, 2012, http://www.bls.gov/data/.

25 Lisa B. Kahn, The Long-Term Labor Market Consequences of Graduating from College in a Bad Economy, (Yale School of Management, 2009), http://mba.yale.edu/faculty/pdf/kahn_long-termlabor.pdf.

26 Andrew Sum, Mykhalo Trubskyy, and Sheila Palma, The Great Recession of 2007–2009, the Lagging Jobs Recovery, and the Missing 5-6 Million National Labor Force Participants in 2011 Why We Should Care, (Chicago: Center for Labor Market Studies Northeastern University, 2012), 21, http://www.northeastern.edu/clms/wp-content/uploads/Lagging-Jobs-Recovery-Report-jan-2012.pdf.

27 Belfield, Levin, and Rosen, The Economic Value of Opportunity Youth, 1.

28 John M. Bridgeland and Jessica A. Milano, Opportunity Road: The Promise and Challenge of America’s Forgotten Youth ̧ (Civic Enterprises & America’s Promise Alliance, 2012), 33, http://www.serve.gov/new-images/council/pdf/opportunity_road_the_promise.pdf.

29 Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration, "PY10 National Summary of Performance Data," Table H1, http://www.doleta.gov/performance/results/#wiastann.

30 JobCorps, "Office ofg JobCorps Quarterly Highlights Report," JobCorps, http://www.jobcorps.gov/Libraries/pdf/10_4th_qtr.sflb.

31 YouthBuild USA., "Research," https://youthbuild.org/research.

32 Bridgeland and Milano, Opportunity Road, 32.

33 Funding level for Youth Opportunity Grants in 2000 retrieved from Clinton archive: The White House Office of Press Secretary, "The Clinton-Gore Administration: An Opportunity Agenda for America's Youth," (2000), http://clinton6.nara.gov/2000/02/2000-02-19-radio-address-paper-on-opportunity-agenda-for-american-youth.html.

34 National Priorities Project estimate of sequestration's impact on youth training programs.