Corporate Tax Inversions and Our Ailing Tax Code

By

Robin Claremont

Posted:

|

Taxes & Revenue

Photo by JeepersMedia on Flickr

Tax avoidance. Economic patriotism. Fairness. Over the last few weeks, these words have been part of the debate over so-called “tax inversions,” hinging on the question of what tax obligations American corporations like Walgreens should have when they benefit from American consumers, economic activity, and infrastructure.

Inversion refers to the practice of a company moving its business address overseas by purchasing or merging with a foreign company, while maintaining its operations and consumer base in the U.S. This allows the company to avoid paying U.S. taxes. Big names such as Walgreens and Pfizer are the most recent to express interest in joining a list of 76 corporations that have already moved their addresses overseas – including well-known brands Fruit of the Loom, Tim Hortons, and Sara Lee.

But what do inversions mean for U.S. taxpayers? Put simply, they mean less revenue from corporate taxes, which translates into less overall revenue available for the U.S. Treasury to pay for the things our nation needs, like unemployment insurance, infrastructure improvements, Social Security, and food assistance.

According to Americans for Tax Fairness, the cost of just one corporate inversion, Walgreens, would mean a loss of $4.6 billion in potential tax revenue over five years. Siphoning off billions of corporate tax dollars could mean a higher tax burden for individual taxpayers in order to make up for that loss.

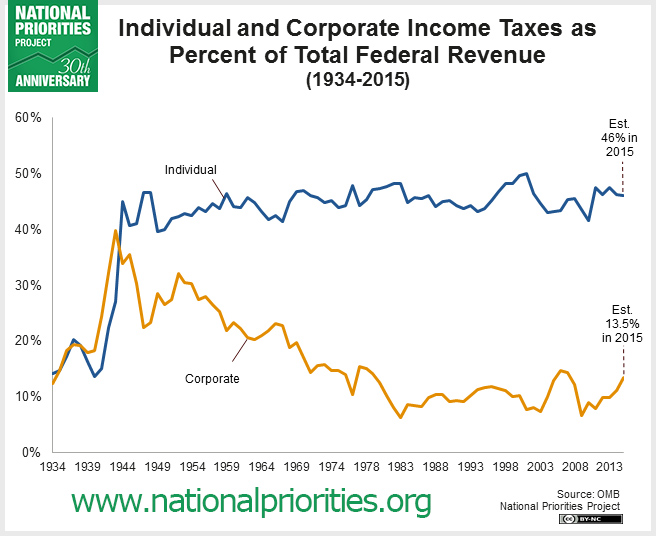

American corporations have long had a lower tax rate than individuals – inverting is just another scheme corporations can exploit in order to lower or eliminate their tax responsibility. Corporate taxes as a percent of total federal revenue has declined significantly over the past fifty years, while the individual share of our nation’s budget has held relatively steady.

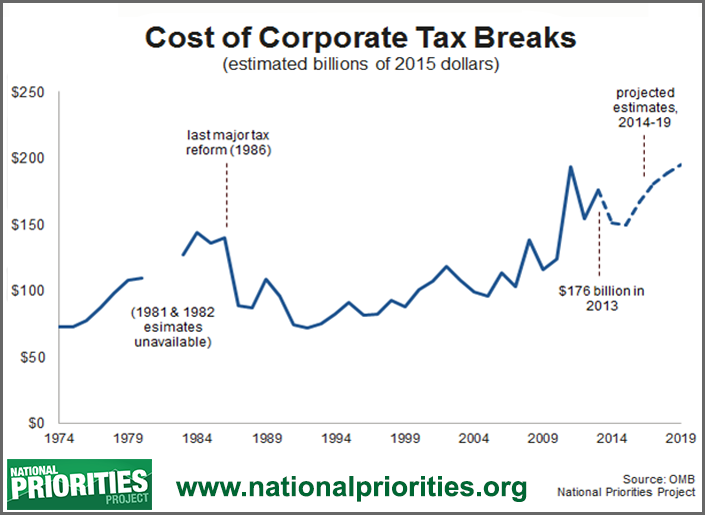

In fact, our recent analysis of tax breaks shows that in 2013 alone, the U.S. lost about $176 billion in potential corporate tax revenue, thanks to a variety of deductions, credits, and exclusions. That’s a 134 percent increase in the size of corporate tax breaks over the last two decades (in 1993, the cost of corporate tax breaks totaled about $75 billion).

Lawmakers spend a lot of time bickering over how to spend federal dollars, but don’t pay much attention to how those dollars come in. Tax inversions are just a symptom of a larger problem ailing our nation: our broken tax code. Smart budgeting is not only about reining in wasteful spending; it’s also about creating revenue streams to pay for the programs and investments that make our nation great.

Before more companies decide to renounce their corporate “citizenship,” Congress needs to find ways to encourage everyone to pay their fair share.